Ernest Hemingway was the reason I first sat down and tried to write. I was sixteen and a newly minted high school dropout. I lived with a single mother on the south side of Atlanta. My work consisted of bagging groceries and stocking shelves at the Winn-Dixie for most of the week while I studied for the GED in the evenings. I didn’t have a particularly clear idea how I would get to a better place in the world, but an inner voice told me that picking books that had this way of refusing to let go was a hell of a good way to start.

Like a lot of young men, I was drawn to the straightforward muscular punch of his style. It was easy to fly through his books. Probably too easy. It was a dangerous pleasure to become caught up in the propulsive qualities of those relentless declarative sentences, often at the expense of weighing the silences he left in his stories where much of his more important meaning was found. And there was the great, paradoxical combination of his subject matter, at once familiar and exotic. Familiar to me in the descriptions of rivers and woods and the coming-of-age in an environment of the field and camp; but exotic in its thrilling depiction of travel and epicurean living that I found enticing. How could you read about flyfishing and drinking good wine on the sere Spanish banks and not want to experience that for yourself?

But there was something else too about his writing that I began to see the longer I read it. There was a depth of loneliness and sadness to almost everything Hemingway ever published. While literary critics liked to talk about minimalism, understatement, and the “iceberg theory,” I saw characters poised on the brink of ruin but somehow refusing to give in. Their only defense against moral and physical extinction was the weird beauty of how they saw the world and how they sought to belong in it.

Much has lately been written about the struggles young men are having in school and their lives. I see it daily in my work as a community college teacher. In recent years, the number of male students in my classes has steadily shrunk, and few of those that do attend appear to have any real idea of what they’re doing there. They have a vague idea that their lives are supposed to be better with the acquisition of credentials, but few have any idea how the pieces connect. Their attendance is frequently spotty and when they begin to fall behind in the assignments, they stop showing up altogether. It’s easy to give something up when you don’t really see the point anyhow.

I try to talk to these young men after class, make them feel welcome. I know what it’s like to not fully trust the academic system. After the Marine Corps, it was disorienting to step onto a university campus. But I didn’t have the traps of multi-player video games and the nihilism of being terminally online. I had those early influences of Faulkner, Wolfe, and Hemingway. I was comfortable spending time inside my own thoughts. I had already learned how reading a true sentence had the power to make your entire world cohere. It was a way to fight the alienation and estrangement I felt in the academic setting that really didn’t know how to handle my experiences as a father and a veteran.

The popular idea of Hemingway held by his detractors is that his books are defined by an inflexible machismo that preens and postures. He putatively denigrates women as a means of displacing his own psycho-sexual anxieties. And while there are moments that are decidedly uncharitable or reductive in his portrayal of women (Margot Macomber in “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” being a conspicuous example), these criticisms quickly veer toward Hemingway’s persona more than his work. In fact, in Hemingway’s best fiction, men are often off-balance and unsure of their moral direction, not in a position to lecture anyone on rectitude. The stories typically hinge on the protagonist’s striving for a set of values that will allow them to live with a clearer conscience. In this way, they are implicitly Stoic, not in the cliched swaggering sense of the term that Hemingway tried to embody in his own troubled life, but in its classical roots. Hemingway’s men are obsessed with living decently in a world where decency is banished. It’s hard to think of a more worthwhile subject than that.

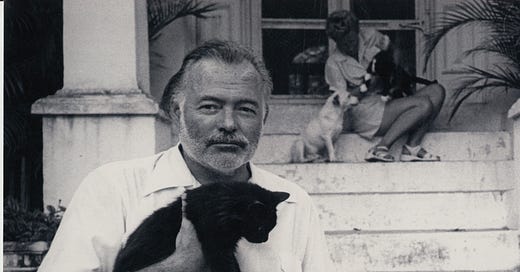

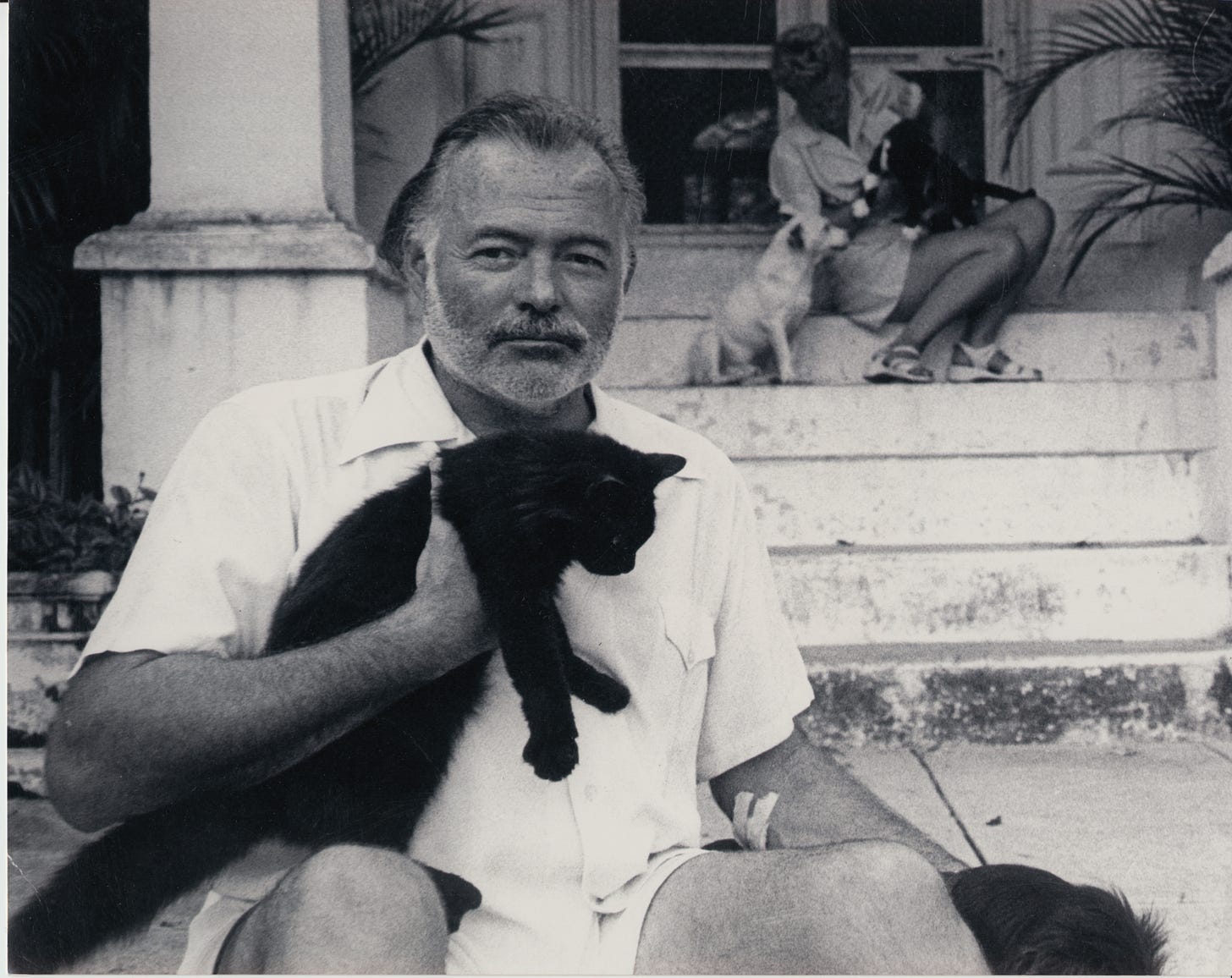

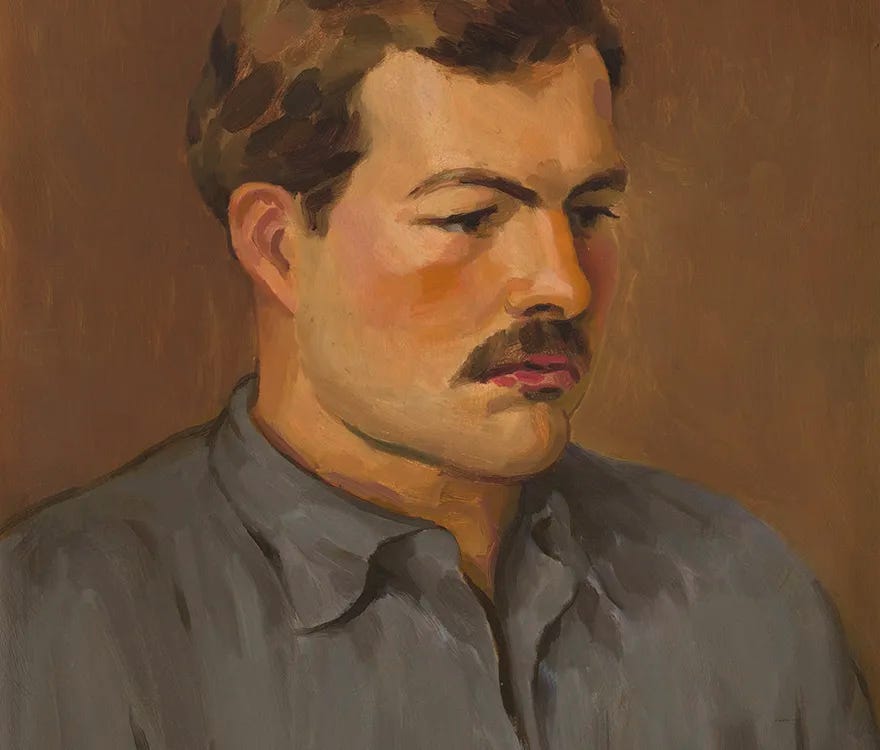

Recent critics and biographers have begun to pay closer attention to the pattern of mental illness that appears to have been a consistent part of Hemingway’s life. You certainly don’t have to look hard. The consistent recklessness and sometimes downright odious behavior is hard to miss. One incident in the Florida Straights where he was reported to have shot with a Thompson submachine gun his initials into the nose of a shark was particularly hard for me to take. Yet, balanced against this, we have personal accounts of those that were his friends who said that there was another Hemingway: a man who was as thoughtful and sensitive as the voice that comes through in so many of those closely observed stories. And there were the later years where mental struggles were increasingly clear after years of head injuries and a fatal daily dose of alcohol. He seems to have been a man deeply hurt and aware of the torture of being trapped inside his own soul.

These young men that I see on campus today are defined largely by their bewilderment and inability to address it. If they are attracted by anything in the Hemingway influence, it’s more likely in line with the worst parts of his legacy. The bluff manner and drunken boasting. What many today might consider a “red-pilled” view of masculinity. But if they were to actually read him and discover a character like Nick Adams growing toward manhood, I believe they might find an important solution to their own struggles.

In the forward to the anniversary edition to INVISIBLE MAN, Ralph Ellison talks about how he learned to shoot birds on the wing from when he read Hemingway as a young man. He says that aside from the excitement of the stories themselves, Hemingway quite literally helped him put food on the table. Maybe young men today could find that reading Hemingway will provide them with skills of a similar kind; we would all be better for it.

The Big Two Hearted River, as often as I read it, never fails to cheer me up because it is so beautiful. Same with The Old Man and the Sea. My very favorite "boy" books are only a little off the beaten track. For example, aren't Tolstoy's Anna Karenina and War and Peace really "boy" books, with the characters of Levin and Pierre front and center? And what is The Brothers Karamazov if not a "boy" book? Thank you for the thoughtfulness of your post—wonderfully written! I think if we were to stack all the writer's biographies in a pile, except maybe a few really good ones like William Jackson Bate on Keats, I would be happy to be the one to light the match.

I have to admit I have neglected Papa, except for reading For Whom the Bell Tolls and the Sun Also Rises. I’ve never read the Nick Adams’ stories. I must rectify that.